Introduction

In the study of the Qing Empire (1644–1912) during the long eighteenth century, historians have traditionallyviewed the dynasty as primarily land-based, with its focus directed toward securing its expansive continentalborders, particularly in Central Asia and the northern steppes. The Qing’s military campaigns, governancestructures, and territorial expansions into regions such as Xinjiang and Tibet have often dominated scholarlydiscussions. Consequently, the empire’s engagement with the maritime world was, until recently, treated asa peripheral concern, largely limited to considerations of southern port cities or the regulation of sea trade, particularly in relation to the European presence in China. However, this image of the Qing as a largely inward-looking, land-centric power has increasingly come under scrutiny in recent historiography.

In the past few decades, historians have started to re-evaluate the Qing dynasty’s relationship with the maritime world, revealing a far more complex and interconnected vision of Qing governance.1 This shift has opened up new avenues of inquiry that move beyond the conventional confines of sea trade and port cities. Scholars have argued that the Qing state was more invested in maritime affairs than previously acknowledged, and this has profound implications for our understanding of late imperial Chinese governance and its relationship to the broader global context. Qing emperors, administrators, and military forces engaged not only in trade but also in the active management of coastal regions, regulation of sea routes, and defence against piracy—all critical components of their imperial strategy to govern an empire with both land and maritime borders.2 My own research has also argued that the Qing, during the long eighteenth century, should be more properly situated within a maritime context.3 However, I would like to reiterate that my aim is not to argue that the Qing was a sea power in the early modern era. Rather, my goal is twofold: first, to examine how the Qing, as a continental power, engaged with the maritime world; and second, to bring into sharper focus the connection between the Qing Empire and the sea prior to the outbreak of the First Opium War.

This revisionist approach has also expanded the geographic scope of inquiry beyond the traditional focus on southern regions like Guangdong and Fujian, which were central to European trade interactions. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of the entire Chinese seaboard, extending from the Bohai Gulf in the north to the Zhejiang coast in the east. This expanded lens reveals that maritime China in the late imperial era was not limited to the south but involved multiple regions, each contributing to the empire’s maritime policies and strategies. This wider perspective enriches our understanding of the Qing’s maritime engagements and reveals the varied ways in which different coastal regions interacted with both the empire and the broader maritime world.

Furthermore, the Qing Empire’s maritime connections were not limited to its internal concerns but were part of a broader redefinition of maritime China in its late imperial era. This redefinition encompasses the Qing’s complex relationships with neighbouring powers such as Japan, Korea, the Ryukyu Kingdom, and Southeast Asian states, as well as its interactions with Western powers like Britain and the Netherlands. The maritime world of the eighteenth century was a space of both connection and disconnection, filled with exchange, conflict, and negotiation, in which the Qing played a significant role in shaping and responding to these dynamics. Through comprehensive maritime policies, trade regulations, and military interventions, the Qing positioned itself as an indispensable player in the regional and global maritime context.

This article, though brief in scope, seeks to critically examine the shifting perspectives and trends surrounding the Qing Empire’s connection to the maritime world in the long eighteenth century. It attempts to argue that recent historiography has significantly challenged the earlier, narrow view of Qing China as predominantly land-focused, instead uncovering a dynamic and multifaceted engagement with the seas. Through an exploration of the expanded geographic range of recent studies, the strengthened ties between Qing governance and maritime concerns, and the redefinition of maritime China during this period, I hope to offer some insights into the Qing’s role in the global maritime world. In doing so, this article also reflects on how these historiographical shifts prompt us to reconsider late imperial China’s strategies for managing its borders according to its specific priorities and circumstances.

Questioning the Land-Focused Image of the Qing Empire

For much of the twentieth century, historians portrayed the Qing dynasty as a fundamentally land-based empire. This view was shaped largely by its extensive military campaigns, territorial expansions into Central Asia, and the administration of vast continental frontiers. Scholars focused heavily on the Manchu conquests of regions like Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia, cementing the Qing’s reputation as a powerful land-based empire.4 Consequently, its interaction with the maritime world was often relegated to the margins, viewed as reactive measures to external threats or as limited engagement with European merchants in southern China, specifically in Canton (Guangzhou). While the traditional narrative captured key aspects of Qing expansion and governance, it overlooked the significant maritime dimension of Qing statecraft, which was vital to the empire’s control over its coastal regions and its broader interactions with the expanding global market.

One of the major reasons behind this land-centric portrayal lies in the sources that were traditionally emphasized. Much of Qing history has been told through the lens of court documents, military treatises, and reports or albums on territorial campaigns in Central Asia and the northern frontiers. These documents naturally highlighted the Qing’s efforts to secure and expand its land borders, leading scholars to prioritize these themes. However, in recent decades, as scholars have delved deeper into the imperial archives and uncovered a sizable number of documents related to maritime matters, a different picture of the Qing has emerged. At the same time, they began to examine other types of primary sources, including maritime customs records (not to be confused with the Customer Service system of the nineteenth century), local gazetteers, private writings written by scholar officials, and regional sites such as carvings on stones or rocks, and inscriptions on coastal temples.5 These sources reveal that the Qing, far from being indifferent to maritime matters, was actively engaged in managing its coastal territories, building naval defences, and, above all, interacting with the sea on its own terms in various ways.

An important shift in thinking about the Qing’s maritime engagement stems from the realization that the empire’s geographical and political challenges extended beyond land. The long Chinese coastline, stretching from the northern Bohai Gulf to the southern tip of Guangdong, was both a frontier and a lifeline for the empire. The coastal regions were vulnerable to piracy, foreign invasion, and smuggling, all of which required the Qing to pay considerable attention to maritime governance. Moreover, maritime commerce, both domestic and international, played a crucial role in the Qing economy. In addition to the renowned “Pearl of the East” Canton, Fuzhou, Ningbo, Dengzhou, and Tianjin were bustling centres of trade that connected China to the broader global economy from time to time throughout the eighteenth century, making it impossible for the Qing to ignore the significance of the sea.

One illustrative example of the Qing’s maritime engagement is the empire’s response to piracy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While most pirates of the time were considered minor threats, the rise of piracy along the southern coast, particularly in Guangdong and Fujian, posed significant disruptions to Qing sovereignty and commerce, with coastal communities bearing the brunt of the impact. The Qing government, as reflected in imperial edicts issued by the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors, was compelled to repeatedly launch naval campaigns to combat and suppress these pirate gangs.6 Even toward the end of the eighteenth century, when the Qing court struggled to maintain firm maritime control, local officials remained persistent in negotiating with the infamous pirate leader Zheng Yi and his successor, Zheng Yi Sao (widely known in Western sources as Ching Shih), in efforts to preserve peace and order along the empire’s seaboard. Whether these actions were practical or successful is another matter, but they demonstrate that the Qing’s anti-piracy efforts were pursued consistently, both in times of relative stability and in more chaotic circumstances.

When discussing the problem of piracy, one cannot overlook the development of Qing naval power during the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong reigns. On various occasions, these emperors emphasized the importance of the sea to the dynasty’s broader strategic goals. While the three emperors are often remembered for their campaigns in Inner Asia, they also took significant steps to strengthen Qing naval capacity, such as in response to the threat posed by the remnants of the Ming loyalist regime based on Taiwan, led by Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), as well as to be cautious about potential threats, including the Japanese and some European seafaring powers based in Southeast Asia, that might be arriving from the sea. The successful Qing conquest of Taiwan in 1683 was a pivotal moment in the consolidation of Qing power, both on land and sea. It not only brought the strategically important island under Qing control but also marked the beginning of more systematic Qing attention to maritime defence and governance.

Furthermore, the Qing’s maritime engagement extended beyond military and administrative concerns to include diplomacy and foreign relations. Qing rulers were acutely aware of the need to manage their interactions with maritime powers, particularly European states such as Britain and the Netherlands. Although the Qing initially restricted European trade to the port of Canton, this was not merely an act of isolation, but rather a strategic decision to control foreign interactions while maximizing economic benefits. The Canton system, which governed European trade with China from the mid-eighteenth century, reflects the Qing’s careful balancing act between maintaining sovereignty and engaging with the global maritime economy. Historians have also argued that foreign traders, for their part, found the system advantageous, viewing Canton as the ideal place to conduct business with the Chinese.7 In other words, European traders had little incentive to venture beyond Canton or sail further north for trade prior to the Macartney Mission of 1793. The system evidently functioned effectively for much of the eighteenth century, as it fulfilled the needs of European traders while allowing the Qing to regulate the flow of goods and foreigners into China, ensuring that merchants adhered to Chinese laws and customs.

In addition to its maritime engagements, recent scholarship has highlighted significant parallels between the Qing’s approaches to its Inner Asian and maritime frontiers.8 Both frontiers—one defined by the vast steppe and desert regions of Central Asia, the other by the expansive coastline and sea routes—presented the Qing dynasty with similar challenges in terms of sovereignty, control, and integration into the imperial system. Researchers have increasingly recognized that Qing rulers adopted comparable strategies in consolidating power over these diverse, often unruly borderlands. For instance, both the maritime and Inner Asian frontiers were marked by a reliance on military force to suppress rebellion and external threats, as well as by the strategic use of deliberate policies to manage relations with powerful local elites and foreign actors. In the Inner Asian frontier, this was evident in the Qing’s negotiations and alliances with Mongol chieftains, while in the maritime frontier, the Qing leveraged local coastal elites and foreign merchants to secure order and promote commerce.9

Moreover, the Qing’s approach to consolidating control over these frontiers involved a dual focus on military and administrative integration. In both cases, the Qing established garrisons, fortified key positions, and implemented systems of governance that integrated frontier regions into the broader imperial structure. Just as the conquest of Xinjiang in the late eighteenth century involved the construction of new administrative networks and military outposts, the incorporation of Taiwan and the regulation of coastal regions after the conquest of Koxinga’s regime in 1683 followed a similar pattern. In both frontiers, the Qing sought not only to pacify and control these regions but also to integrate them into the empire’s economy and governance structures. This process of consolidation reflected the Qing’s broader imperial strategy of combining force with accommodation, ensuring that both maritime and inland frontiers were effectively brought under its control.

These similarities underlie a broader historiographical shift in understanding the Qing as a flexible and adaptive early modern empire that effectively balanced both land-based and maritime concerns. Rather than treating the Qing’s Inner Asian and maritime frontiers as entirely distinct, recent scholarship has emphasized how both were central to the dynasty’s consolidation of power. This more integrated perspective reveals the Qing’s ability to manage diverse frontier regions through similar strategies of military, administrative, and economic control, showcasing its capacity to navigate the complex geopolitical realities of early modern empire-building. By examining these frontiers in tandem, we gain a more comprehensive picture of the Qing’s multifaceted approach to governance, one that transcends the traditional land-sea dichotomy and reflects broader evolving of imperial consolidation in the early modern world. While this approach is still developing, and it may be too early to determine its full impact, it marks a promising step toward a more integrated understanding of the Qing Empire’s frontier management, both on land and at sea.

Expanding the Geographic Focus Beyond Southern China

Until recently, scholarly attention on Qing China’s maritime engagement has been largely concentrated on southern regions, particularly Guangdong and Fujian—what I have elsewhere termed “Southeast China centrism.”10 This regional emphasis was understandable, as these provinces were key hubs of maritime trade and the main points of interaction with European merchants, notably through the Canton trade system. However, recent scholarship has broadened the geographic scope, recognizing that focusing solely on southern China presents an incomplete picture of the Qing Empire’s maritime strategies and governance. By extending analysis to the entire Chinese seaboard, including northern and eastern coastal regions, historians have uncovered a more comprehensive understanding of the Qing dynasty’s engagement with the maritime world. This expanded focus highlights the importance of regions such as the Bohai Gulf, the southern and eastern coasts of the Shandong peninsula, and Zhejiang, emphasising that maritime China in the Qing period was not monolithic but regionally diverse, with each coastal area playing a distinct role in the empire’s maritime policies.

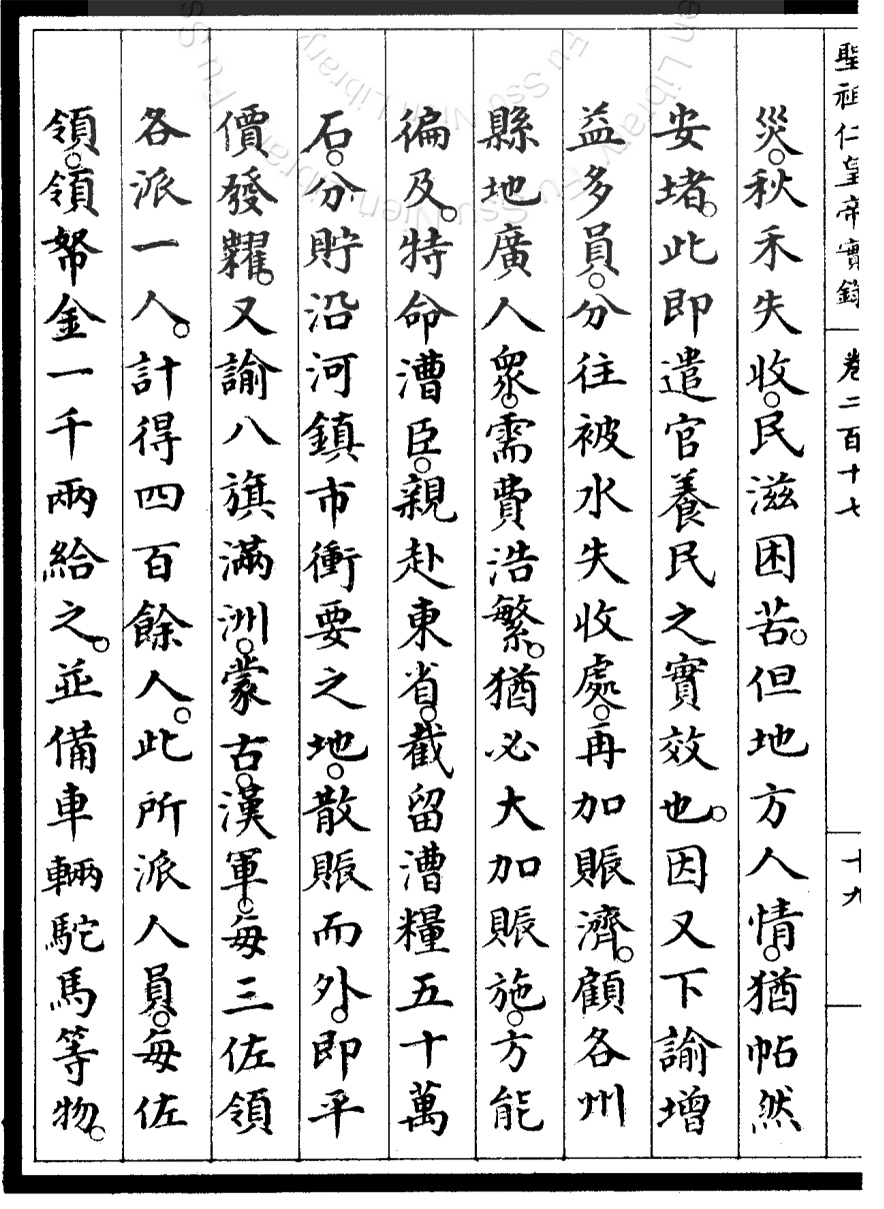

A key driver of this historiographical shift has been the realization that northern coastal regions, particularly those around the Bohai Gulf, played a crucial role in the Qing’s maritime defence. While Guangdong and Fujian were central to foreign trade and diplomatic interactions with European powers, northern China was vital to domestic maritime commerce and defence against potential threats, whether from Japanese invaders or local piratical forces. The Bohai Gulf, situated between present-day Liaoning and Shandong provinces, was not only a key fishing and salt-producing area but also a strategic location for the Qing military. Its proximity to Beijing, the imperial capital, and Manchuria, the Manchu homeland, further spoke to its significance. Defensive fortifications and naval patrols established in the region were crucial in protecting these strategic and symbolic areas from potential maritime incursions.The recent discovery of sea charts (see fig. 1) and private documents related to Sino-Korean private trade further highlight the Bohai and Yellow Seas as critical zones of exchange and interaction. As noted in the Chaoxian wangchao Yingzu shilu,

Since the transport of grain by sea in the Dingchou year, the Chinese people familiar with the sea routes have engaged in harvesting sea cucumbers. Every year, around the late summer and early autumn, they sail to the western seas, making this journey a yearly routine. The number of those who go has steadily increased, and no one knows exactly how many hundreds of vessels are involved. Although local officials and border commanders wish to pursue and expel them, they are outnumbered, and at times they resort to offering wine and provisions to entice them to leave. Those who understand the situation are deeply concerned. 11

Fig. 1. Haijiang yangjie xingshi quantu (compiled in the late eighteenth century) features the Miaodao Archipelago, which geographically guards a strategiccorridor entering the Bohai Gulf.

Although these activities were considered illegal and problematic from an administrative standpoint, the extract above reveals that private, non-state trade was quite widespread between China and Korea. This trade, albeit illegal, contributed to the region’s economic vitality and strengthened the shadow market linking the two countries. In this context, the Qing’s engagement with its northern maritime frontier becomes crucial for understanding the dynamics across the sea space near their power base.

In addition to its defensive importance, northern China’s maritime economy also constituted a significant segment of the Qing Empire. The region’s coastal communities were deeply involved in fishing, salt production, and shipping—industries that contributed significantly to both the local and national economies. For instance, the salt production in Shandong was one of the largest in China, and the industry was strictly regulated by the Qing state, which derived substantial revenue from it. Along with sea salt, seaweed cultivation also thrived along the Liaodong Peninsula. In his Jilin waiji, for instance, Sa Ying’e recorded,

Seaweed (haizao), found in the East China Sea, is black and tangled like hair, with leaves resembling those of common algae (zao), hence its name. According to traditional herbal texts, there are two types: one that grows in shallow waters, short and black like a horse’s tail and the other that grows in the deep sea, with large leaves resembling vegetables. The Tangshu, in its Bohai chapter, mentions that seaweed from the southern seas is also known as kombu. Although the names differ, they refer to the same type. Today, the seaweed produced in Hunchun is quite abundant.12

This passage put forward the richness of northern China’s maritime resources, specifically seaweed, which was not only a source of food but also of medicinal and economic value. The reference to haizao in the Tangshu and its mention of kombu from the southern seas suggest a long-standing recognition of the importance of marine products across different regions of China. The abundance of seaweed in Hunchun, as noted by Sa Ying’e, reflects the prosperous nature of the region’s maritime industries during the Qing period. The cultivation and trade of such resources further suggest the significance of the northern coast in the broader Qing economic system, demonstrating that the maritime economy of northern China was not necessarily secondary to that of the south. Instead, it played an integral role in sustaining both the local population and the empire’s broader economic framework.

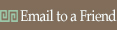

Furthermore, the northern ports played a crucial role in the domestic grain trade, with shipments of rice and other staples flowing northward from the fertile southern provinces to feed the population of Beijing and its surrounding areas, particularly when the canal system was damaged or under repair. Additionally, during times of famine or natural disasters in the northern maritime provinces, relief materials were arranged and transported to affected areas by sea. An example is the natural disaster that struck the Shandong Peninsula in 1704 during the late Kangxi era, as recorded,

The autumn harvest failed, and the people have become increasingly destitute. However, the local populace remains calm and orderly, which is a testament to the successful efforts of officials in supporting and nurturing the people. In light of this, another decree was issued to dispatch additional officials to regions affected by the floods and crop failures, in order to further provide relief. Given the vast territories and large populations of the various prefectures and counties, the expenses required are enormous. Yet, it is essential to increase the relief efforts to ensure aid reaches all affected areas.

As a special directive, the provincial grain officials have been ordered to personally travel to the eastern provinces and withhold 500,000 shi of grain from the annual transport quota, storing it in key towns along the river. Additionally, one person from every three companies of the Manchu military was dispatched, totalling more than 400 individuals. Each company received 1,000 taels of silver along with vehicles, camels, and other necessary supplies, and these individuals were sent to various prefectures and counties in Shandong to continue the relief efforts. The duration of this relief work was set to last until July of the following year.

As for the prefectures of Dengzhou, Qingzhou, and Laizhou, grain was to be transported by sea from Tianjin, with each prefecture receiving 30,000 shi. Furthermore, three high-ranking officials were appointed to oversee and inspect the relief efforts along three routes, ensuring that aid was distributed properly.13

Fig. 2. An excerpt of the Shengzu renhuangdi shilu Fig. 2. An excerpt of the Shengzu renhuangdi shilu

(please refer to note 13)

This excerpt highlights how the Qing state, through its maritime capabilities, was able to mobilize resources efficiently and respond to natural disasters in the northern provinces. The use of sea routes for transporting grain and other essential supplies underlines the role the northern maritime regions played in supporting not only local economies but also in maintaining the overall stability of the empire. Maritime governance in these areas was not just about defence and trade but also a vital part of disaster management and state relief efforts, ensuring that even the most remote coastal regions were connected to the central mechanisms of imperial power.

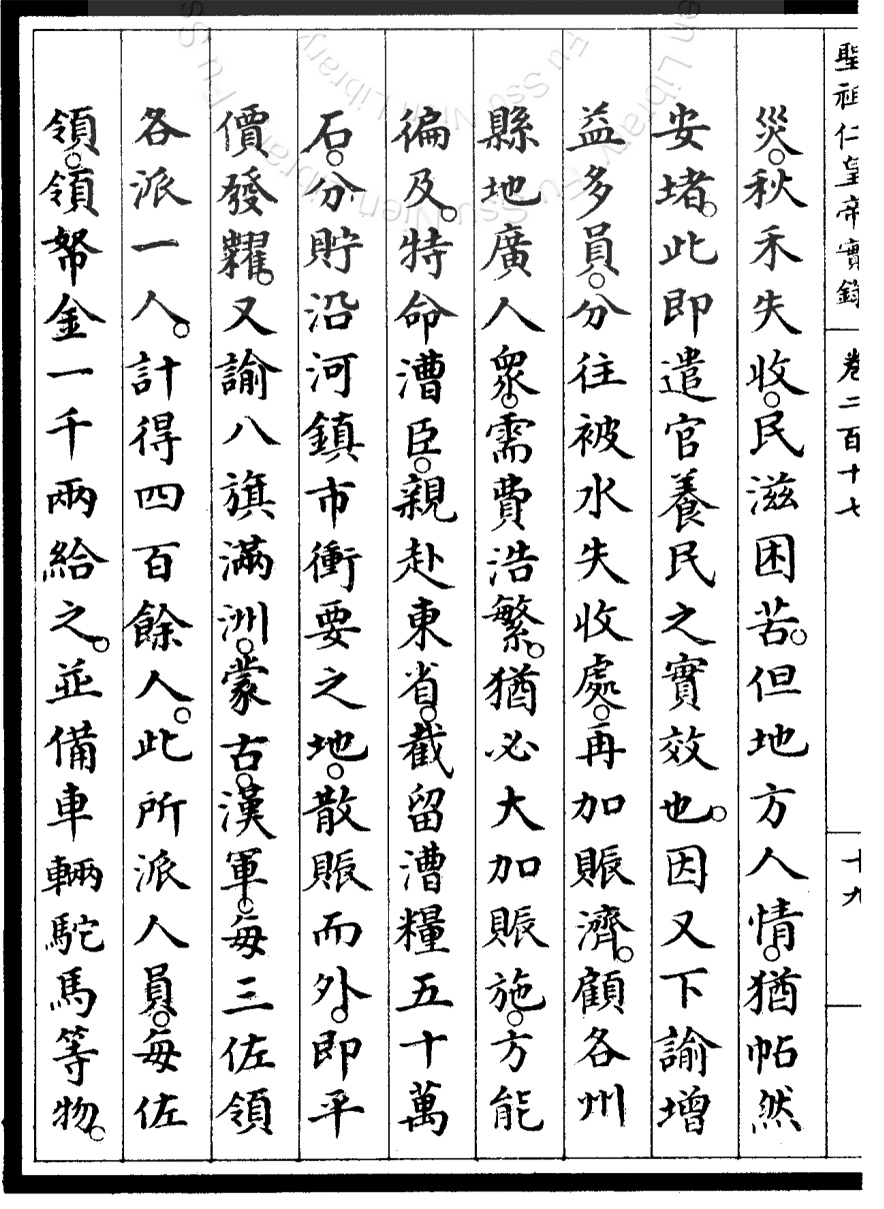

Another region that has gained increased attention in recent historiography is Zhejiang, which, though located in eastern China, was distinct from the more heavily studied southern provinces. Zhejiang was both a centre of trade and a hub of intellectual activity, with its coastal cities, such as Zhapu, playing a critical role in the empire’s engagement with the East Asian maritime world. Zhapu, in particular, was important for trade with Japan, highlighting the diversity of Qing maritime interactions beyond the southern ports. The city was also a centre for trading Chinese commodities that linked Zhejiang’s economy either through Canton to global markets, or directly from Zhejiang to Japan.14 Moreover, scholars have increasingly emphasized that Zhejiang’s economic and cultural flourishing was largely due to its strong maritime connections with Japan.15

The growing attention to Zhejiang also sheds light on the fact that intellectual and cultural exchanges in the maritime world were not confined to the south. The region was home to numerous influential scholars and officials who contributed significantly to Qing governance and intellectual life. For example, officials from Zhapu and nearby areas were instrumental in advising the court on coastal defence and maritime policy, drawing on local knowledge of the sea and its economic importance. This intellectual engagement shows that the Qing’s maritime world was not just about economic and military governance but also involved sophisticated policy discussions and the application of local expertise. These regional officials played a key role in shaping the Qing state’s understanding of the maritime world, making Zhejiang a crucial player in the broader imperial maritime strategy.

Fig. 3. The seascape of Zhapu as depicted by the British following the Battle of Chapu in 1842. Illustration by Thomas Allom and G. N. Wright from China, in a Series of Views, Displaying the Scenery, Architecture, and Social Habits of That Ancient Empire, vol. 3, (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1843), p. 49.

Furthermore, the maritime history of northern and eastern China reveals both commonalities and regional variations in how the Qing state managed its coastal populations and resources. In the south, particularly in Guangdong and Fujian, Qing officials focused primarily on regulating foreign trade and controlling smuggling. Similarly, in the north, there was an emphasis on maintaining security and promoting domestic economic activity. However, differences in governance emerged, particularly in how the state addressed specific regional concerns. For instance, the Qing’s regulation of salt production in the Bohai Gulf and its investment in coastal defence in Shandong reflect a distinct set of priorities compared to those in the south. These differences illustrate that the Qing’s approach to maritime governance was neither uniform nor unidirectional, but rather adapted to the specific conditions and challenges of each region.

By expanding the geographic scope of analysis, historians have begun to redefine what is meant by “maritime China” in the late imperial era. Previously, maritime China was often equated with the southern regions, particularly the bustling port cities of Canton and Amoy (Xiamen). However, the recognition that northern and eastern China also played a crucial role in the empire’s maritime strategy challenges this narrow definition. In this broader view, maritime China encompasses the entire coastline, with each region contributing to the empire’s maritime governance in distinct ways. This more inclusive definition offers a deeper understanding of the Qing state’s relationship with the sea, revealing that maritime China was not solely about trade with the West or the so-called “Nanyang connection,” but was a complex, multifaceted entity that involved domestic commerce, regional defence, and interactions with neighbouring Asian powers. While much focus has been placed on Sino-Japanese or Sino-Korean relations, the Qing-Ryukyu relationship is also worth examining. However, due to the constraints of word count, I encourage readers, if I may, to explore this topic further in one of the chapters of my forthcoming monograph, which is expected to be released in October this year.16

This broadened geographic focus has significant implications for how we understand the Qing state’s approach to maritime governance. The Qing dynasty, far from being solely focused on the southeast, maintained a more comprehensive and flexible maritime strategy that accounted for the distinct challenges and opportunities presented by each coastal region. Whether in the north, where security and resource extraction were primary concerns, or in other regions, the Qing’s engagement with the sea was far more nuanced and varied than earlier studies have suggested. This recognition of regional diversity enriches our understanding of the Qing as a maritime power that managed its coastline and maritime frontier in ways that were both adaptive and regionally specific.

As a result, the expansion of the geographic focus from southern China to include the entire Chinese seaboard marks a critical shift in our understanding of Qing maritime governance. By considering the importance of northern and eastern coastal regions, historians have uncovered new dimensions of the Qing’s relationship with the maritime world, revealing a more inclusive and regionally diverse approach to maritime governance. This expanded perspective challenges earlier, southern-centric narratives and provides a more holistic view of how the Qing state managed its vast coastline, integrating military, economic, and intellectual strategies in ways that were tailored to the specific needs of each region. Thus, this broader geographic lens redefines our conception of maritime China and deepens our appreciation of the Qing dynasty’s multifaceted engagement with the sea.

Concluding Remarks

The Qing Empire’s relationship with the maritime world during the long eighteenth century has undergone a substantial reassessment in recent historiography, leading to a redefinition of “maritime China” that transcends its earlier geographical limitations. Traditionally confined to studies of southern China and its interaction with European traders, our understanding of the Qing’s maritime engagement has now expanded to encompass the entire Chinese coastline, from the Bohai Gulf in the north to the Zhejiang coast in the east, and beyond to the South China Sea. This broader geographic focus, as discussed in earlier sections, reveals the rich diversity of regional maritime policies and strategies that played a critical role in the Qing’s imperial governance.

The analysis of northern coastal regions, such as the Bohai Gulf and Yellow Sea, demonstrates that Qing maritime concerns extended far beyond southern trade hubs like Guangdong, highlighting the need to move beyond discussions largely dominated by the Canton system. Recent discoveries, including sea charts and private documents related to Sino-Korean trade, have revealed the significance of northern maritime zones for both economic exchange and security. At the same time, the renewed focus on Zhejiang in studies of Qing maritime governance demonstrates how eastern China was integrated into the empire’s naval defence and contributed to the formation of an intellectual identity tied to the sea, further complicating the previously southeastern-centric narrative. These insights collectively encourage us to view maritime China as a diverse and regionally interconnected entity, crucial to the Qing Empire’s domestic and international strategies.

This redefinition, however, extends beyond mere geographical expansion. It invites a conceptual rethinking of maritime China, allowing us to explore how the Qing’s engagement with the sea intersected with broader imperial concerns such as territorial control, security, and state-building. As demonstrated, the Qing’s maritime policies were not limited to economic regulation or defensive strategies. Rather, they were integral to the Qing’s approach to consolidating power, managing coastal and overseas populations, and integrating frontier regions into the imperial fold. Coastal regions, from the salt-producing hubs of Shandong to the fishing communities along the Bohai Gulf, were not only economically vital but also politically significant for maintaining internal stability and securing the empire’s borders. Control over these seafaring activities can also be seen as an effort to project sovereignty across maritime spaces.

Moreover, the Qing’s maritime governance reflects a broader imperial strategy that resonates with its land-based policies in Inner Asia. In both contexts, the Qing sought to integrate diverse frontier regions through a combination of military force, administrative governance, and cultural co-optation. The successful conquest of Taiwan and subsequent naval campaigns against piracy demonstrate how maritime strategies were not isolated from the empire’s overall efforts to project power and consolidate authority. This parallel between maritime and land-based strategies reinforces the idea that the Qing saw its maritime frontier as crucial to maintaining the empire’s broader territorial and political integrity.

This broader conceptual understanding of maritime China offers an opportunity to revisit how we think about empire-building in the Qing period. The Qing’s efforts to govern its maritime frontier were not only reactive measures to external threats or economic opportunities but were proactive strategies that played a fundamental role in shaping the Qing’s identity as an Asian empire. This approach allowed the Qing to navigate the complexities of maintaining sovereignty over diverse territories while engaging with an increasingly interconnected world. The evolving maritime policies, from regulating private trade to engaging in diplomatic relations with both Asian and Western counterparts, showcase the Qing’s flexibility in managing its maritime frontier in ways that were deeply intertwined with its broader imperial objectives.

* I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS) for hosting me as a CCK-APC Visiting Scholar at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. My sincere thanks go to Professor Lai Chi Tim, Dr. Michelle Jia Ye, and Kenny Chau for ensuring that my stay in Hong Kong was both seamless and enjoyable.

Notes

- For recent trends in the oceanic turn in Qing studies in the United States, see Xing Hang, “The Evolution of Maritime Chinese Historiography in the United States: Toward a Transnational and Interdisciplinary Approach,” Journal of Modern Chinese History 14, no. 1 (2020): pp. 152–171.

- For two recent studies on the Qing Empire and the issue of piracy, see Robert Antony’s The Golden Age of Piracy in China, 1520–1810: A Short History with Documents (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022) and his forthcoming work Outlaws of the Sea: Maritime Piracy in Modern China (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press).

- Ronald C. Po, The Blue Frontier: Maritime Vision and Power in the Qing Dynasty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). The Chinese edition of The Blue Frontier, revised and refined, will be available on shelves in November this year, published by National Taiwan University Press.

- See the widely cited Peter Perdue, The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), and the classic James A. Millward, Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759–1864 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998). See also Pamela Kyle Crossley, “The Qing Unification, 1618–1683,” in East Asia in the World: Twelve Events That Shaped the Modern International Order, eds. Stephan Haggard and David C. Kang (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 129–145; and Dittmar Schorkowitz and Ning Chia, eds., Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

- During my recent visit to CUHK, I learned that Professor Paola Calanca, based at ICS, is working on a promising project featuring carvings on rocks in Fujian. This study holds great potential to shed new light on the field of maritime China.

- For details, see, for instance, Chen Yuxian, Haifenyangbo: Qingdai huan dongya haiyu shang de haidao (Xiamen: Xiamen daxue chubanshe, 2018).

- Leonard Blussé, “Review Article on Gang Zhao’s The Qing Opening to the Ocean: Chinese Maritime Policies, 1684–1757,” American Historical Review 119, no. 3 (June 2014): p. 869.

- Scholars such as Ling-Wei Kung and Cheng-Heng Lu from Taiwan have actively promoted this endeavour. For example, see the workshop titled “Revisiting Ming-Qing China from Inner Asian and Maritime Perspectives,” organized at Academia Sinica on June 7, 2023.

- I would also recommend interested readers to explore an online article by Ling-Wei Kung titled “Tongguo neiya he haiyang kan Qing shi yanjiu,” accessed 10 September 2024, https://lingweikung.com/posts/inner-asia-maritime-qing.

- Ronald C. Po, “A Port City in Northeast China: Dengzhou in the Long Eighteenth Century,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 28, no. 1 (January 2018): p. 162.

- Chaoxian wangchao Yingzu shilu, juan 38, May 5, 1734, 13b. For Sino-Korean sea trade in the long eighteenth century, see Zhang Haiying, “14–18 shiji Zhong-Chao minjian maoyi yu shangren,” Shehui kexue 3 (2016): pp. 139–148.

- Sa Ying’e, Jilin waiji, juan 7 (Taipei: Xinwenfeng chubanshe, 1985), 17a.

- Shengzu renhuangdi shilu, juan 217, Kangxi 43 nian, October 14, pp. 19b–20a. See also fig. 2 for an excerpt of the original text.

- For the significance of Zhapu in Asian history, see the extensive studies by Akira Matsuura and Liu Shiuhfeng.

- See Feng Zuozhe, “Zhapugang yu Qingdai Zhong-Ri maoyi wenhua jiaoliu,” accessed 10 September 2024, http://www.historychina.net/qsyj/ztyj/zwgx/2004-06-29/25533.shtml.

- Ronald C. Po, Shaping the Blue Dragon: Maritime China in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2024).

|

Fig. 2. An excerpt of the Shengzu renhuangdi shilu

Fig. 2. An excerpt of the Shengzu renhuangdi shilu