How did China smell to European travellers in the past? T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) argues that “the first condition of understanding a foreign country is to smell it” because feeling “truly” is the first condition of thinking “rightly.”1 Feeling and thinking are undeniably intertwined, and how China smelled was also interlinked to the changing Western images of the country over centuries. China was generally admired during the times of Marco Polo (1254–1324), sixteenth-century Portuguese and Spanish adventurers, seventeenth-century Jesuit missionaries, and Enlightenment philosophers. However, from the late eighteenth century onward, during the golden age of Western colonialism and imperialism, European popular imaginations gradually formed a negative image of China. These shifting attitudes and sensibilities significantly influenced how China was perceived and smelled. While Spanish priest Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza (1545–1618) described in his 1585 book that the Chinese, both in their streets and their houses, were marvellously clean,2 the Englishman George Wingrove Cooke (1814–1865) quoted a contemporary French Jesuit anecdotally, who remarked: “Alas! madam, in China there is but one scent, and that is not a perfume.”3 Does a country carry a distinctive smell? It might be challenging to scientifically prove that; yet it is a common trope in travel literature that contributes to the stereotyping or “othering” of a particular country, its people, and its environments. Under the noses of European travel writers of the nineteenth century, China had her own peculiar smell.

The True Chinese Smell

The source of the perceived authentic Chinese smell varies in different narratives. Clarke Abel (1780–1826), a British surgeon and naturalist who served as the chief medical officer on Lord Amherst’s embassy to China in 1816–1817, was one of the first nineteenth-century travellers to meticulously document Chinese smells. While strolling along the long, dirty streets near the capital Beijing (Peking), Abel noticed a scene that “gave so peculiar a character to the streets”: fur cloaks with long sleeves hanging before the doors, possessing what he perceived as “the true Chinese smell.”4 He did not provide an explanation for why he considered this odour to be truly Chinese. In fact, most Han Chinese people would strongly disagree with his view, regarding such a smell “barbaric” instead, as their own preferred winter dresses were made of odourless cotton and silk. This story serves as an illustration of cross-cultural misperceptions that feed into the formation of olfactory stereotypes.

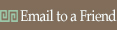

A more common source of the reputed distinctive Chinese smell was the bustling streets of the densely populated cities and towns (Figure 1). During an expedition along the east coast of China, British Army medical officer Charles Alexander Gordon (1821–1899) found himself overwhelmed by the odours that assailed his nostrils on the crowded streets of Guangdong (Canton): they were “not only different in nature from all other stenches,” but also “no less extraordinary by reason of their variety—all different from each other, and from all others; they were, in fact, purely and thoroughly Chinese.”5 The renowned Scottish photographer John Thomson (1837–1921) was more elaborate on the composition of the true Chinese smell in his portrayal of the business quarter of Fuzhou (Foochow), a city on the southeastern coast of China:

The atmosphere also is oppressed with odours, in their variety and sublimated offensiveness peculiarly Chinese; the unsavoury outcome of extremely defective drainage, which blends its exhalations with the fumes of charcoal, garlic, and oil; whiffs of opium and tobacco being mingled therewith by way of an occasional change.6

While this blend of odours may have shocked the foreigner’s “delicate sensibility,”7 in Shanghai’s native city, where quaint little shops lined the narrow passages, the greasy pavement exhaled “the rich, close, and altogether peculiar odour so familiar to all old residents in the Celestial Empire.”8 A decade later, as “the new order of things” began to emerge in the new republic of China, the streets still retained “the grime and the smells,” all “typical of Old China.”9 The true smell of China, as it was, may have endured beyond the vicissitudes of historical change, leaving a lasting impression in the memories of travellers.

Although the writers keenly endeavoured to preserve these ephemeral whiffs in words, they also claimed that the peculiar odour of China was unimaginable, an experience that was profoundly bodily and personal. Commenting on the Chinese method of preparing manure as fertilizer, Charles Alexander Gordon wrote: “these places are offensive to sight and smell in a degree that cannot be imagined by people who have never visited China.”10 Scottish female adventurer Constance Gordon-Cumming (1837–1924) made similar remarks about a site offered by the Chinese for the English Church Mission Society’s station. It was in the “foul, overcrowded streets” of Fuzhou, and “what that means, at its very best, can scarcely be realised by any one not personally acquainted with the horrors of a Chinese city.”11 By emphasizing their unique sensory experience of the true Chinese smell, these writers essentialized China, positioning it as the diametrical opposite of “us,” and mythologizing it beyond reach.

Is there such a thing as a “true Chinese smell”? Anecdotal, impressionistic, and subjective depictions of such an odour mainly reflected the fleeting sensations and emotions of the narrators, influenced bya particular mindset. Some other travellers, however, sniffed more attentively and archived specific smells that were characteristic of China, often associated with particular Chinese practices and customs. There was a sardonic statement circulating among foreigners, claiming that “the chief industry of China is the manufacture of smells.”12

The Manufacture of Smells

The most frequently complaint-about stenches “manufactured” by China were offensive atmospheric odours stemming from poorly paved streets and malfunctioning sewers, two primary targets in modern sanitation campaigns.13 However, these were hardly exclusive to China, as medieval European cities and towns were similarly miasmic and industrializing Europe of the nineteenth century also had its share of foul odours. Another high-profile malodour was allegedly the body odour of the Chinese, attributed to a lack of regular baths and hygienic products, and dietary and clothing habits. However, Caucasians were not deemed agreeable to the Chinese nose either, a deeply rooted stereotype documented even in the same corpus of travel writing.14 So, what were the characteristic stenches manufactured in China?

There was a “peculiarly obnoxious” smell “without which no Chinese city is complete,” derived from the “primitive methods” of manure collection.15 Utilizing human excrement to fertilize soil was a common practice in the Chinese agricultural tradition, giving rise to a balanced rural-urban ecosystem, an ever-flowing cycle of exchange between agricultural products and human waste.16 Despite his admiration for the Chinese way of cultivating the soil with extreme care and attention to details, the sinologist James Dyer Ball (1847–1919) commented on the collection of night-soil in the cities and even in every little hamlet, “to the disgust of the olfactory nerves of those unaccustomed to such an ancient mode.”17 Records of stenches “manufactured” in relation to this practice are innumerable in Western travel literature. A street scene in 1880s Hangzhou, as observed by the English missionary Arthur Evans Moule (1836–1918), was a symphony of exotic sound and smell: the shouts of the scavengers, carrying the sewage of the city “in open buckets” to their country boats, were accompanied by “the multiform and most evil odours.”18 Amid the bustling crowd of a Canton street, some men trotted along “bearing most objectionable and unfragrant uncovered buckets, inclining foreigners to believe that Chinamen were created without the sense of smell.”19

Another exceedingly “outlandish” aspect amongst the array of Chinese stenches was connected to a Chinese burial custom, according to which coffins had to be rested in the house until the most propitious day of interment arrived. The English missionary Samuel Pollard (1864–1915) provided a vivid account of how this primarily Han Chinese burial method entailed “revolting unsanitariness and almost nameless horrors”:

What can be more horrible and offensive than to walk into the front room of some Chinese friend’s house and to be offered a seat near an awkward-looking mound right in the centre of the room. As the cup of tea is handed to you and you are sipping it and inquiring after the welfare of the members of the household, you are conscious of a disagreeable smell which tends to get on one’s nerves and make one feel ill. And when you find it comes from the mound in the centre of the room, and that under this, resting on the floor, is the coffin and corpse of the father who died six months ago and has never yet been carried out for burial, you feel very queer. Fancy keeping the corpse of one’s father or husband in the sitting-room for twelve months or more!20

Constance Gordon-Cumming’s sensitive nose detected an odour of a similar nature. During her travels to Beijing, she encountered the funeral procession of a man who had been dead for about two months. Since the heavy wooden coffin had not been properly sealed, she was “nearly poisoned for half an hour afterwards by the appalling stench which floated along the track in his wake.”21 This Chinese practice is indeed notably stench-inducing, but the scent of death is universal. John Barrow (1764–1848), a member of Lord Macartney’s embassy to China (1792–1794), noted that the Chinese bury their dead at a proper distance from the dwellings of the living, whereas the Europeans “not only allow the interment of dead bodies in the midst of their populous cities, but have thrust them also into places of public worship, where crowded congregations are constantly exposed to the nauseous effluvia, and perhaps infection, arising from putrid carcases.”22

Dried fish, with a distinctively unpleasant odour to the average foreign palate, represented another unique source of stench “manufactured” by China (Figure 2). The clichéd “spoiled, stinking fish” even found its place in Kant’s work as an example of the eating habits of Asian people.23 Clarke Abel, during his 1810s journey in China, observed that the lower class of Chinese consumed “rice or millet, seasoned with a preparation of putrid fish that sent forth a stench quite intolerable to European organs.”24 Subsequently, this pungent smell permeated the pages of travel literature. The British surgeon Frederick Treves (1853–1923) likened dried fish shops in Guangzhou to “depots for discarded museum specimens” and the stench emanating from them was “beyond words.”25 An influential travel handbook introduced the fishing port of Ningbo with a cautionary note about “the pervasive odor of drying cuttle-fish” that wafted with “nearly every breeze that blows over the town” each spring.26 The odour of Chinese fishermen’s squid-drying fields in California even triggered a lengthy legal dispute in the 1890s regarding the residency rights of the Chinese in Monterey. Intertwined with existing discourses of racial difference (i.e., the notion that Chinese were inherently repugnant), subjectively perceived offensive smells became the legitimate accused parties in the institutionalized exercise of power.27

Amongst all the stereotypical Chinese odours, the smell of opium might be most complex, intertwined with rich political and moral undertones (Figure 3). Virtually a sensorial symbol of China in the nineteenth century, opium smelled evil and represented China’s illness, moral degeneration, and shame. British missionary Edwin Dukes (1847–1930) remarked on the pervasiveness of opium in Chinese inns, calling it “a great nuisance…for the smell of the fumes is very vile and sickening.”28 When discussing hiring chair-bearers, he wrote, “one is obliged to look at them—and shall I say, smell them?—to calculate whether they shek-in (eat smoke) .”29 The nose was engaged in making both practical and moral judgements simultaneously. However, the moral judgement was not necessarily directed solely at the Chinese. In fact, there was no shortage of criticism from home and some church leaders in England even labelled the opium trade a “national sin.”30 Therefore, the perception of the fumes of opium as baneful, wicked, and abominable might have resulted from the coordination of feeling and thinking. Opium does not inherently have a sickly smell; in fact, during its heyday when opium was a symbol of taste relished by the privileged classes in China, it smelled fragrant, as illustrated in a poem written by the future emperor Daoguang 道光 (1782–1850) in the early nineteenth century:

Sharpen wood into a hollow pipe,

Give it a copper head and tail,

Stuff the eye with bamboo shavings,

Watch the cloud ascend from nostril.

Inhale and exhale, fragrance rises,

Ambience deepens and thickens

When it is stagnant, it is really as if

Mountains and clouds emerge in distant sea.31

The polarized olfactory perception of opium demonstrates that the sense of smell is more ambivalent than commonly assumed, begging for carefully contextualized readings and interpretations. Amidst the vast array of stenches “manufactured” in China, it’s worth noting that China also boasted a profusion of scents appreciated by European noses of the time.

Nature’s Incense

“The Chinese are fond of flowers,” as observed by the English missionary Mary Bryson (?–1913). Sweet floral scents—what she referred to as “Nature’s incense”—seemed “for a time almost to overpower the vileodours which rise from the crowded streets of every Chinese city.”32 The seasonal cycle of Chinese flowers and their fragrances were documented at great length in the writings of Alicia Little (1845–1926, aka Mrs Archibald Little):

Among wild flowers the narcissus and the banksia bloom in March and April, when the rocky hills become red with azaleas for hundreds of miles, wisteria hanging there in festoons. In April also beans are in flower, and these with the yellow blossoms of the oil-plant make it indeed a fragrant month. In May the country air is sweet with wild honeysuckle and dog-rose. In June follows the luscious gardenia, sold in the streets for one cash a blossom (a tenth of a penny), and worn at this season by every woman, rich and poor alike, in her hair. In July among the mountain glades large white lilies are to be found, with a rich fragrance, but in this as in some other instances, it is a private and local breath, not a pervading odour such as those specially enumerated. In September and October, however, and even in August for some early flowering varieties, the delightful Olea fragrans and Kuei-hua scents the air in city and country alike, not to speak of the favourite jasmine, white and yellow. November and most of December are practically scentless in North China, but in mild seasons at the end of December, and generally in the early part of January, the sweet Lah mei, or waxen almond (cheimonanthus fragrans) blooms before its leaves appear; and it is scarce over before the delicious white and pink double almond, richly fragrant, breathes out the old year for the Chinese, this generally occurring in February. 33

One of the most sweet-smelling flowers mentioned by Little is the gardenia. Native to tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, Madagascar, and Pacific islands, there are five species in China. The flowers are often nocturnal and are usually “strongly sweetly fragrant” with a distinctive odour.34 This overpowering scent was found in an Englishman’s garden in Shanghai when the renowned botanist Robert Fortune (1812–1880) paid a visit to this newly opened treaty port in 1848. Fortune wrote that this species, noted as the “new Gardenia (G. Fortuniana),” had been introduced by the Horticultural Society to England in 1845 and was now common in English gardens. In the Shanghai garden, the bushes were “covered with fine double white flowers, as large as a camellia, and highly fragrant.”35 The heavy, delicious aroma of the gardenia also delighted the British adventurer Isabella Bird-Bishop (1831–1904) as she travelled across the Yangtze valley in China. “Strings of gardenia blossoms hang up at that season in all houses, every coolie sticks them into his hair, and even the beggars find a place for them among their rags,” as she observed.36

In the same garden in Shanghai, Robert Fortune also discovered ( or “sniffed out”) large quantities of the “Olea fragrans, the Qui Wha” planted in different parts of the garden. In autumn, when they are in bloom, the air is “perfumed with the most delicious fragrance.”37 The perfume is so intense that “one tree is enough to scent a whole garden.”38 Also featured in Alicia Little’s passage as well, Olea fragrans is more commonly known as Osmanthus (Guihua 桂花 or Muxi 木樨 in Chinese). Out of a total of 30 species, 23 are indigenous to China. As a well-known spice plant, the flowers are fragrant in all species. 39 Fortune noted that Osmanthus flowers were a source of great profit, cherished by the Chinese for multiple purposes. Ladies wear wreaths of them in their hair, and dried petals are used for “mixing with the finer kind of tea, in order to give it an agreeable perfume.”40

Another favourite scent employed by the Chinese to flavour tea is jasmine. Native to India, Jasminum sambac is widely cultivated in South China for its fragrant flowers, which are used in tea flavouring and in perfumes.41 When visiting nurseries in Tianjin, accompanied by Robert Fortune, the medical officer Charles Gordon recognized the Jasminum sambac and the Olea fragrans, “two of the plants whose flower buds are employed to give their peculiar odour to certain kinds of scented tea.” These flowers are also used to adorn ladies’ hair and to scent the apartments of the wealthy during winter, with “the flower buds being for this purpose collected in considerable numbers, and placed in an open saucer upon the table. 42 Clearly, European knowledge of Chinese olfactory practices was expanding in those decades following the Opium War. The intoxicating aroma of jasmine also provided relief to travellers’ noses weary of fetid street odours. The city walls of Ningbo were thickly covered with “fragrant jessamine and wild honeysuckle,” making leisurely strolls joyful for Constance Gordon-Cumming.43 On Orphan Island in Poyang Lake, where a stately temple was located during Mary Bryson’s impromptu visit, it was “like a garden, the grey old rocks being covered with lovely climbing plants, while the fragrance of the Chinese jessamine scented the air.”44

Blooming in winter or very early spring, the sweet Chimonanthus praecox (Lamei 臘梅) and the delicious Armeniaca mume (Meihua 梅花, or plum blossom; referred to as almond by Alicia Little) hold particular cultural significance to the Chinese, as their delicate scents enhance the festive ambience of the Lunar New Year (Figure 4). Mary Bryson noted that for a Chinese florist, in early spring, “he has the fragrant flowers of the la-mei and the delicate pink blossoms of the almond,” accompanied by the “fragrant narcissus” to adorn Chinese homes.45 James Dyer Ball introduced the Chinese practice of displaying aromatic fruit blossoms in his encyclopaedia, a neglected aspect of flower culture in the West:

The Chinese cut off the branches of fruit-trees as they burst into bud, and the delicate tints of the peach, the white flowers of the plum, and the tender blossoms of the almond, are all eagerly sought for, to decorate their homes at that festive season of the year.46

Besides these sweet-smelling flowers particularly cherished by the Chinese, foreigners exploring the “Flowery Land” often marvelled at the diverse scents emitted by magnolias, orchids, lotus flowers, and peonies. In addition to floral fragrances, for nineteenth-century European traders, the medley of “Nature’s incense” in China was incomplete without the subtle aroma of tea, the exquisite perfume of musk, and the agreeable scent of camphor—three of the most sought-after commodities for export to Europe.

While a significant amount of knowledge about the aromas and flavours of tea had been circulating in Europe, the olfactory experiences of our travellers offered fresh insight into the marvellous scent bestowed by nature. In the heart of a five-gorged valley, as French poet Paul Claudel’s (1868–1955) murmuring narrative unfolds, he suddenly found himself in a wood “like that which on Parnassus served for the assembly of the Muses!” Above him, tea plants lifted their shoots and foliage. “A delicate perfume, which seems to survive rather than emanate, flatters the nostril while recreating the spirit. And in a hollow I discover the spring!”47

Musk is undoubtedly one of the most treasured and costly aromatic substances revered in both eastern and western cultures. Marco Polo documented this exquisite scent in his travelogue on several occasions. He detailed the features of musk deer and the methods of obtaining the aromatic substance in the province of Tangut, where “the finest and most valuable musk is procured.”48 In Thebeth (Tibet), as he noted, the animals that produce the musk abounded, “and such is the quantity, that the scent of it is diffused over the whole country.” Throughout every part of this region, “the odour generally prevails.”49 Six centuries later, the same aroma still permeated the accounts of Victorian travellers who encountered the valuable aromatic. According to Isabella Bird-Bishop, Kuan Hsien (Guanxian) was an unattractive town in Sichuan Province, except for its strategic location, which made it a hub for trade with Northern Tibet. Musk was one of the most profitable Tibetan exports traded in this town for Chinese tea, silk, and cotton. From there, it was sold or smuggled to neighbouring cities such as Chongqing and Chengdu. “Chengtu reeks with its intensely pungent odour,” as she wrote.50

Camphor was another well-established fragrant commodity exported to Europe and North America. William Hunter (1812–1891), an American trader based in Canton in the 1820s, mentioned it in a poem à la Byron: “Know’st thou the land where the nankin and tea-chest, / With cassia and rhubarb and camphor, abound?”51 Cinnamomum camphora, evergreen large Scents of China: A Modern History of Smell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023) trees with a strong scent, are the primary source of camphor. Derived from chipped wood of the stems and roots, as well as from branchlets and leaves through steam distillation, camphor is used medicinally as a stimulant, antispasmodic, antiseptic, and so on.52 James Dyer Ball’s encyclopaedia includes an entry on it, identifying camphor as a useful drug originating from the camphor tree, abundant in the provinces of Fuh-kien (Fujian) and Kwong-tung (Guangdong). “The odour of the wood is pleasant, and when fresh and strong of some utility in keeping away moths and insects from clothing.”53

So, was/is there a true Chinese smell? There might be one lingering in each traveller’s memories, but in reality, there is certainly an indefinite array of smells existing in any given country. Many above-mentioned stenches and fragrances identified by the Victorian travellers can be conceived as “Chinese” since they are associated with native species, climate, habits and customs in China. However, once essentialized and stereotyped, they became an instrument of othering within the particular socio-historical contexts. In this sense, a decolonization of the nose might be the first condition of “feeling truly.”

*A draft of this essay was completed during my research stay at the Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS) at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. I would like to thank ICS for the visiting fellowship awarded to me. A slightly different version of this essay will appear in https://odeuropa.eu/encyclopedia/. Some of the sources used in this essay are also discussed in Xuelei Huang, Scents of China: A Modern History of Smell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), chapter 2.

Notes

- T. S. Eliot, “Rudyard Kipling,” in A Choice of Kipling’s Verse Made by T. S. Eliot, With an Essay on Rudyard Kipling, Rudyard Kipling and T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1941), p. 30.

- Juan González de Mendoza, The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and the Situation Thereof, trans. R. Parke, vol. 1 (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1853–1854), p. 27.

- George Wingrove Cooke, China (London; New York: Routledge, 1859), p. 223.

- Clarke Abel, Narrative of a Journey in the Interior of China (London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818), pp. 115–116.

- Charles Alexander Gordon, China from a Medical Point of View in 1860 and 1861 (London: J. Churchill, 1863), p. 70 (emphasis mine).

- John Thomson, The Land and the People of China (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1876), p. 100 (emphasis mine).

- Ibid.

- Thomas Hodgson Liddell, China, Its Marvel and Mystery (London: G. Allen, 1909), p. 38.

- A. S. Roe, Chance & Change in China (London: William Heinemann, 1920), p. 176.

- Gordon, China from a Medical Point of View, p. 152 (emphasis mine).

- Constance F. Gordon-Cumming, Wanderings in China (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, 1888), p. 247 (emphasis mine).

- Gretchen Mae Fitkin, The Great River: The Story of a Voyage on the Yangtze Kiang (Shanghai: North-China Daily News & Herald, 1922), p. 1.

- Xuelei Huang, Scents of China: A Modern History of Smell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), pp. 66–70.

- Ibid., pp. 70–74.

- Roe, Chance & Change, p. 12.

- Xingzhong Yu, “The Treatment of Night Soil and Waste in Modern China,” in Health and Hygiene in Chinese East Asia Policies and Publics in the Long Twentieth Century, ed. Angela Ki Che Leung and Charlotte Furth (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 51–60.

- James Dyer Ball, Things Chinese, or Notes Connected with China (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), p. 22.

- Arthur Evans Moule, New China and Old, Personal Recollections and Observations of Thirty Years (London: Seeley and Co., 1891), pp. 54–55.

- Gordon-Cumming, Wanderings in China, pp. 32–33.

- Samuel Pollard, In Unknown China: A Record of the Observations, Adventures and Experiences of a Pioneer Missionary during a Prolonged Sojourn amongst the Wild and Unknown Nosu Tribe of Western China (London: Seeley, 1921), p. 127 (emphasis mine).

- Gordon-Cumming, Wanderings in China, p. 369.

- John Barrow, Travels in China (Philadelphia: W.F. M’Laughlin, 1805), p. 337 (emphasis mine).

- Immanuel Kant, “Physische Geographie,” in Kant’s gesammelte Schriften, ed. Königlich Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, vol. 9 (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1907), p. 379.

- Abel, Narrative of a Journey, pp. 231–232.

- Frederick Treves, The Other Side of the Lantern: An Account of a Commonplace Tour around the World (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1904), p. 275.

- Carl Crow, The Travelers’ Handbook for China (Including Hongkong) (New York; Shanghai: Dodd, Mead & Co.; Carl Crow, 1921), p. 140.

- Connie Y. Chiang, “Monterey-by-the-Smell: Odors and Social Conflict on the California Coastline,” Pacific Historical Review 73, no. 2 (2004): 183–214.

- Edwin Joshua Dukes, Everyday Life in China; or, Scenes along River and Road in Fuh-Kien (London: Religious Tract Society, 1885), p. 164 (emphasis mine).

- Ibid., p. 165.

- Yangwen Zheng, The Social Life of Opium in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 94–95.

- Quoted in Zheng, The Social Life of Opium, p. 57.

- Mary Isabella Bryson, Child Life in China (London: Religious Tract Society, 1900), pp. 49–50.

- Alicia Little (Mrs. Archibald Little), Round About My Peking Garden (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1905), pp. 34–35 (emphasis mine).

- Tao Chen and Charlotte M. Taylor, “29. Gardenia J. Ellis, Philos, trans. 51: 935. 1761,” in Flora of China, vol. 19, pp. 141–144, accessed 4 July 2023, http://flora.huh.harvard.edu/china/PDF/PDF19/Gardenia.pdf.

- Robert Fortune, A Journey to the Tea Countries of China (London: John Murray, 1852), p. 17.

- Isabella L. Bird-Bishop, The Yangtze Valley and Beyond, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1900), pp. 235–236.

- Fortune, A Journey to the Tea Countries, p. 17.

- Ibid., p. 331.

- “5. OSMANTHUS Loureiro, Fl. Cochinch. 1: 28. 1790,” in Flora of China, vol. 15, pp. 286–292, accessed 4 July 2023, http://flora.huh.harvard.edu/china/PDF/PDF15/osmanthus.pdf.

- Fortune, A Journey to the Tea Countries, pp. 332–333.

- “41. Jasminum sambac (Linnaeus) Aiton, Hort. Kew. 1: 8. 1789,” in Flora of China, vol. 15, p. 318, accessed 5 July 2023, http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=200017788.

- Gordon, China from a Medical Point of View, p. 186.

- Gordon-Cumming, Wanderings in China, p. 305.

- Bryson, Child Life in China, p. 138.

- Ibid., pp. 49–50.

- Dyer Ball, Things Chinese, p. 285.

- Paul Claudel, The East I Know, trans. Teresa Frances and William Rose Benét (New Haven: Yale University Press; London: Oxford University Press, 1914), p. 151.

- Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian, with an Introduction by John Masefield (London; New York: J.M. Dent; E.P. Dutton, 1908), p. 137.

- Ibid., p. 238.

- Bird-Bishop, The Yangtze Valley and Beyond, vol. 2, p. 72.

- William C. Hunter, The “Fan Kwae” at Canton before Treaty Days, 1825–1844 (Shanghai: The Oriental affairs, 1938), p. 67.

- “15. Cinnamomum camphora (Linnaeus) J. Presl in Berchtold & J. Presl, Prir. Rostlin. 2(2): 36. 1825,” in Flora of China, vol. 7, pp. 102, 167, 175, accessed 6 July 2023, http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=200008697.

- Dyer Ball, Things Chinese, p. 126.

|